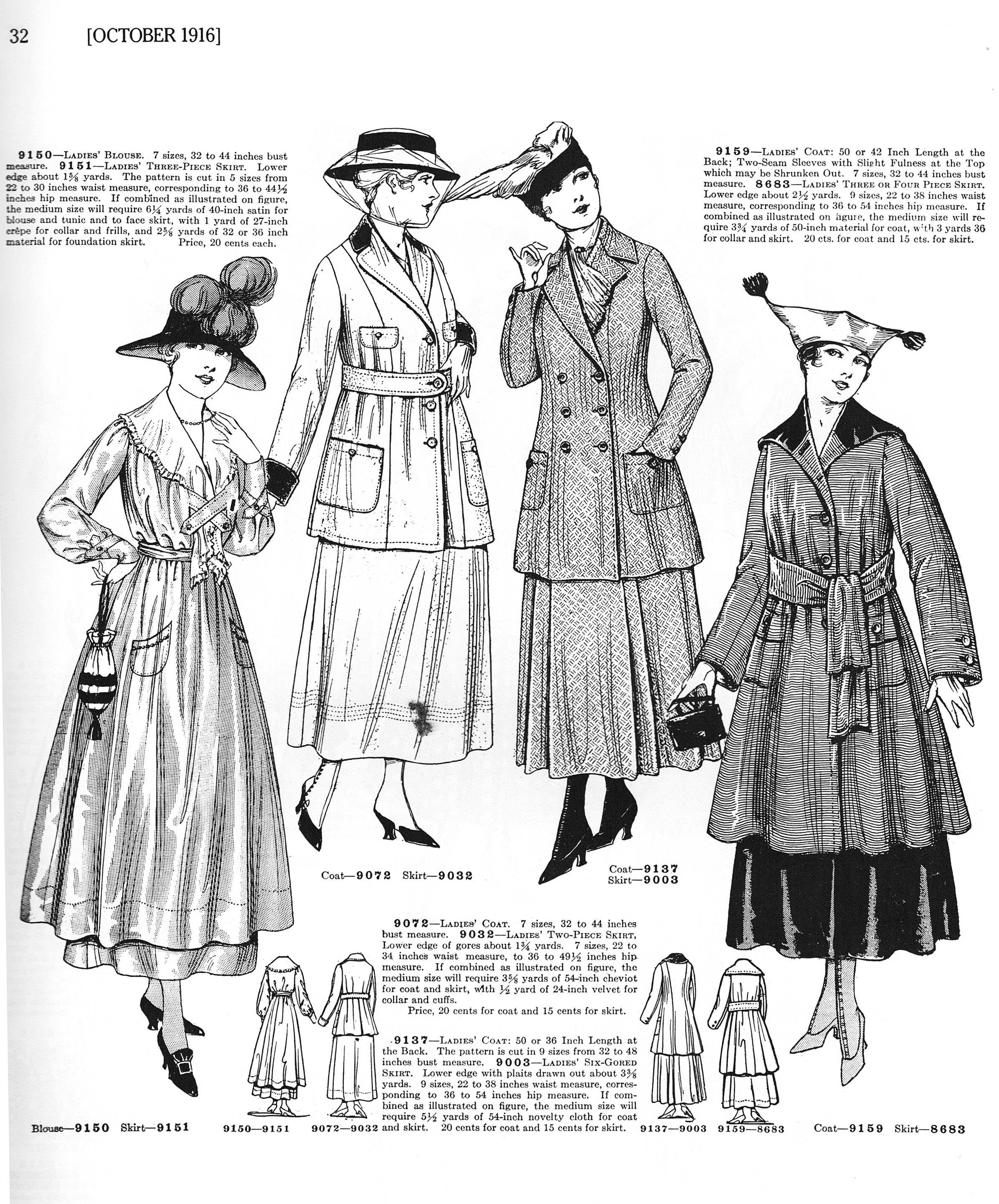

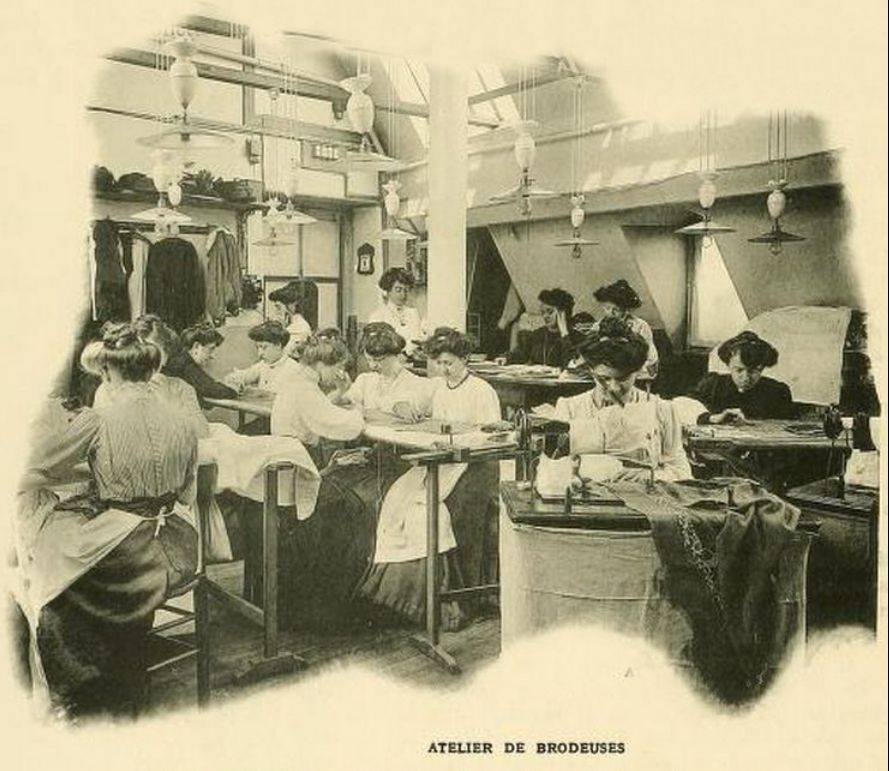

Paris was an exciting place for the fashion industry at the beginning of the century. The House of Worth in the late 19th century had created an image of luxury, style and exquisite needlework for wealthy customers not just from France, but from the Continent, England and the United States. The industry included not just employees, but contract seamstresses, embroiders, and finishers in little ateliers throughout the fashion district. Some of these capable women went on to create their own reputations and their own clientele.

Inside the gown that I was to reconstruct was this label, which led me to discover one of these innovative fashion houses: Callot Soeurs. You can find out more about them at these links:

http://www.fashionintime.org/callot-sisters-history-fashion/

http://www.victoriana.com/GazetteduBonTon/designerdresses.html

Photo of embroiderers from Les Creatuers des Mode, 1910; I do not know if these women were working on gowns for the Callot sisters, but it is possible! Many of these ateliers were on the upper floors of buildings so that they could take advantage of natural daylight from the skylights overhead.

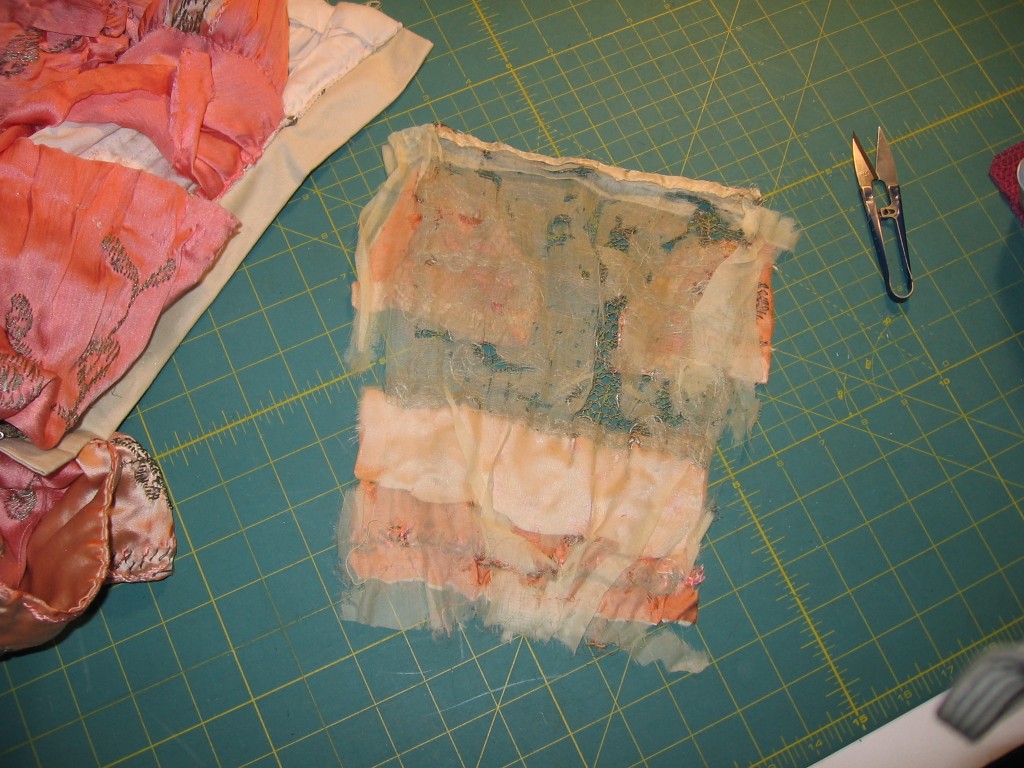

The Callot sisters were known for the use of gold and silver lame and poly-colored embroideries… On this antique bodice the metallic threads have torn the silk fabric. But the wealthy patrons never expected the gowns to last 100 years, so it didn’t matter to them that the metallic threads might damage the silk. These gowns were expected to be ephemeral things, worn only once or twice in the presence of a circle of friends, then packed away, possibly to be brought out again on a voyage or at a resort. The styles changed so quickly in this era that by the next year the lady would order another gown featuring some new and novel design.

The silk embroideries have lasted, so we are able to re-use these lovely pieces.

Silk embroidery on the original gown, shown against the skirt lining. Inside the elaborate drapery I found a straight pin, left there by a long-ago seamstress in Paris.

One of the typical features in many of these late Edwardian gowns is the insert at the front of the bodice. These vestees are often the most distinctive and artistic section of the gown, repeating and embellishing the overall theme. On this gown, the silk backing the vestee has been shattered and broken apart, but the metallic lace was intact.

The “S-curve” silhouette is another trademark of the Edwardian era. You might look at those early photos and wonder how they puffed their chests out like that! This glimpse of the supporting ruffles may answer the question. These ruffles were made of substantial silk satin, gathered to the lining and allowed to support the outer fabric. You can see from the photo that the edges were pinked, not hemmed, and that this section of the dress is still like new after 100 years.

I was reminded of a different approach to garment construction as I studied the lining of this gown. If you look closely at the photo, you will notice that the shoulder strap section is sewn by hand to the body of the lining. The edges were hand hemmed first, and then the entire section was whip stitched along the connecting edges. Our modern method would be to machine these pieces together along a standard seams line, but this couture method gives the designer much more control over the final fit.

I have sometimes read ladies’ complaints about the endless time spent in fittings at the dressmaker’s in journals and letters of earlier times. As we examine the careful attention to a perfect fit, starting with that innermost layer, we can see why the fittings were necessary. This also helps me to understand some of the exorbitant expense of a designer gown. This dress was not pre-cut with dozens of other dresses and then sewn together by machine in an assembly line! This couture gown was created, customized and crafted for only one client. Of course she (or her husband) would pay for that sort of detail!

Note the underarm gusset… Madeleine Vionnet originally worked at the Callot Soeurs house, where this gown was made – imagine her learning to work with this element here, to be carried on later in her revolutionary bias cut gowns?

It’s a strange sensation to disassemble a piece of history. My usual inclination would be to preserve it. But, the client wanted to wear the gown, not merely look at it, and it was not wearable in its present state. It would be too small to fit her, and there would have been the constant threat of further damage. Plus, of course, a large part of this gown had already been removed from the skirt. We can only imagine how grand that section must have been!

I was privileged to be able to take my time in the process and to take clear photos every step of the way. As I worked, I learned.

Next post: the new gown