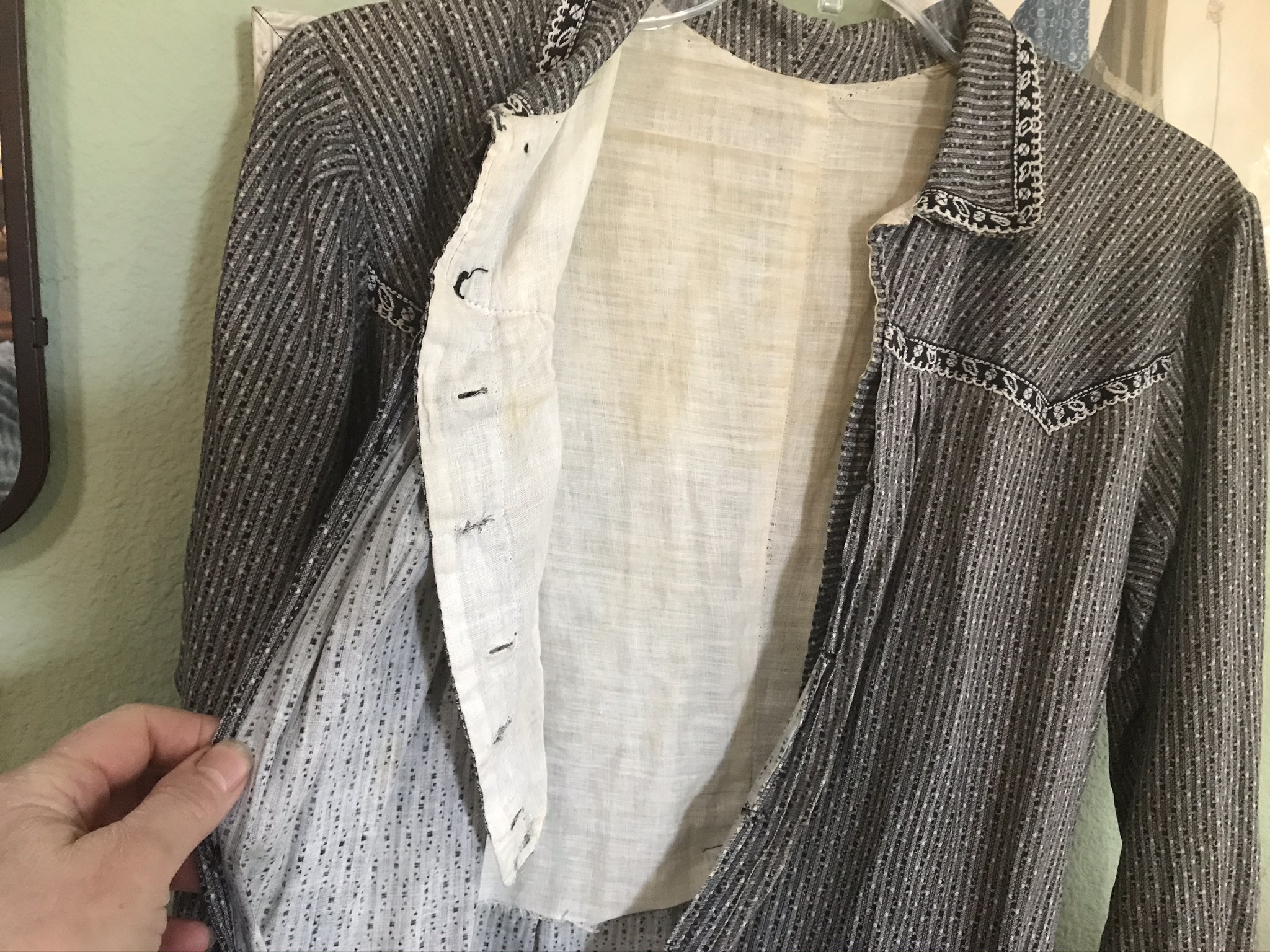

One of the best ways to learn about “what they wore” is to study a garment from the era. I am fortunate to own an antique cotton house dress, circa 1907 – 1909, judging by the style details. It’s a simple garment, with only a bit of trim on the yoke and collar. It has the silhouette of the era, with a flounce at the bottom and gathered sleeves.

Looking at the House Dress

Looking at the House Dress

The yoke is shaped in a “western” style. If you think about it, this dress pre-dates “western” movies and cowboy singers. This shape was a variation on the clothing of the 1890s through 1910s. It was only in the decades after that it became a symbol of the American cowboys.

The lining is made of a thin, open-weave type of cotton. If you look inside, you can see that it’s a mixture of machine stitching and hand sewing. The darts are sewn by hand! And the area at the center front, at the button closure, plus the short plackets at the sleeve cuffs, are stitched by machine. The trim is sewn by machine, as well.

The original dress was made for someone much shorter and smaller than I am, probably about 4’10” tall. I noticed that the original owner found it was too long in front; she took an internal tuck just above the flounce to shorten it.

It’s quite possible that this dress was made for maternity wear. That tuck above the flounce and those hand stitched darts could have been added after the pregnancy, so the new mother could continue to wear the dress.

To make a copy for myself, I started with my own personal sloper for the bodice lining and a sleeve pattern from a 1907 blouse waist that I liked. I was able to draft the front and back by copying the angles and pleats of the original, but with my own measurements for skirt length and back waist. (I tend to be much longer in the waist than most patterns, so this is always an important measurement for me.)

The original bodice lining was attached in a different way than other garments I have seen: the lining pieces were sewn to the fashion fabrics so that the raw edges were enclosed. And yet, the lower edge of the lining was completely unfinished! More than 100 years after it was first worn, the lining is still holding up well.

Making the House Dress

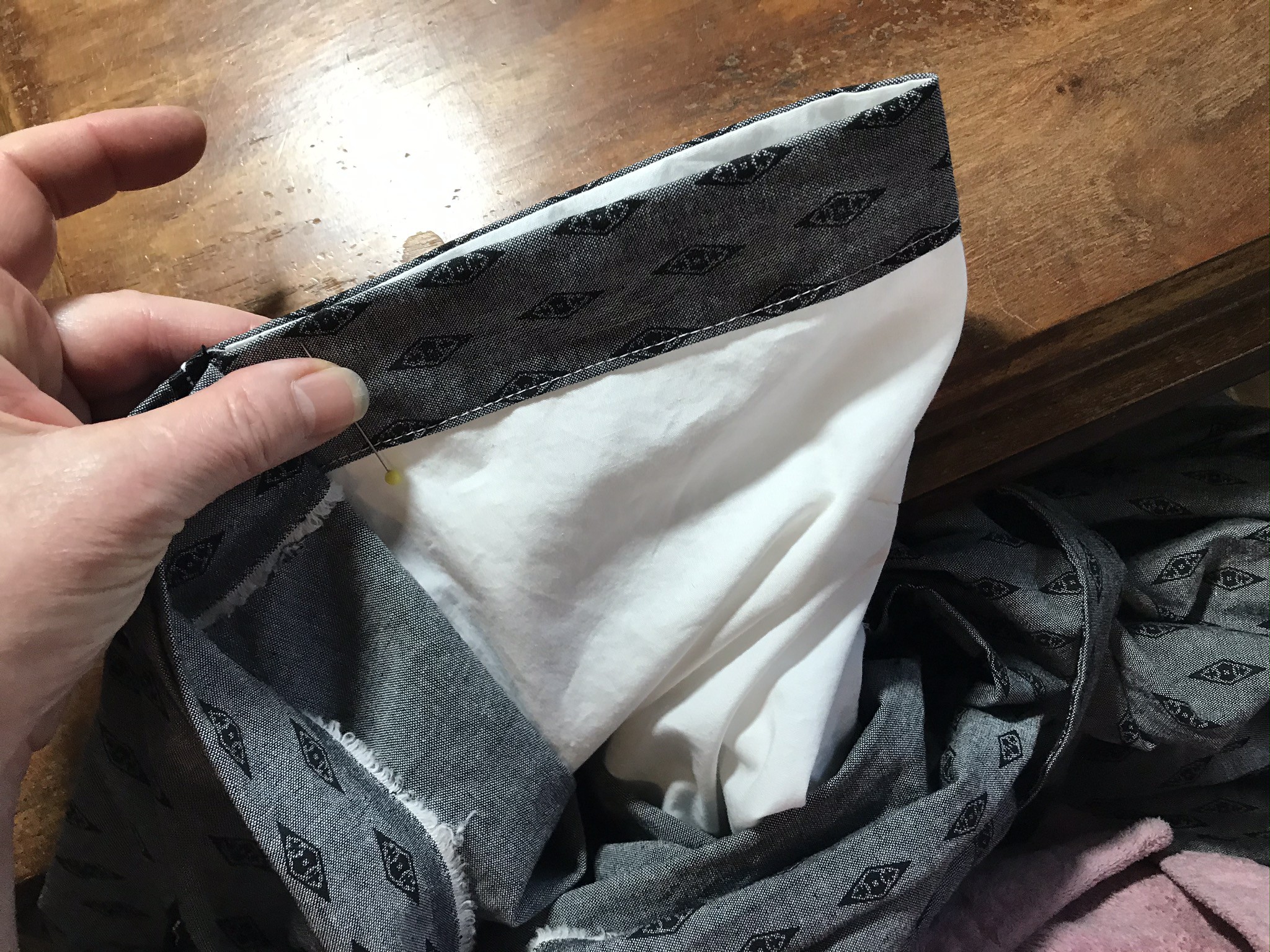

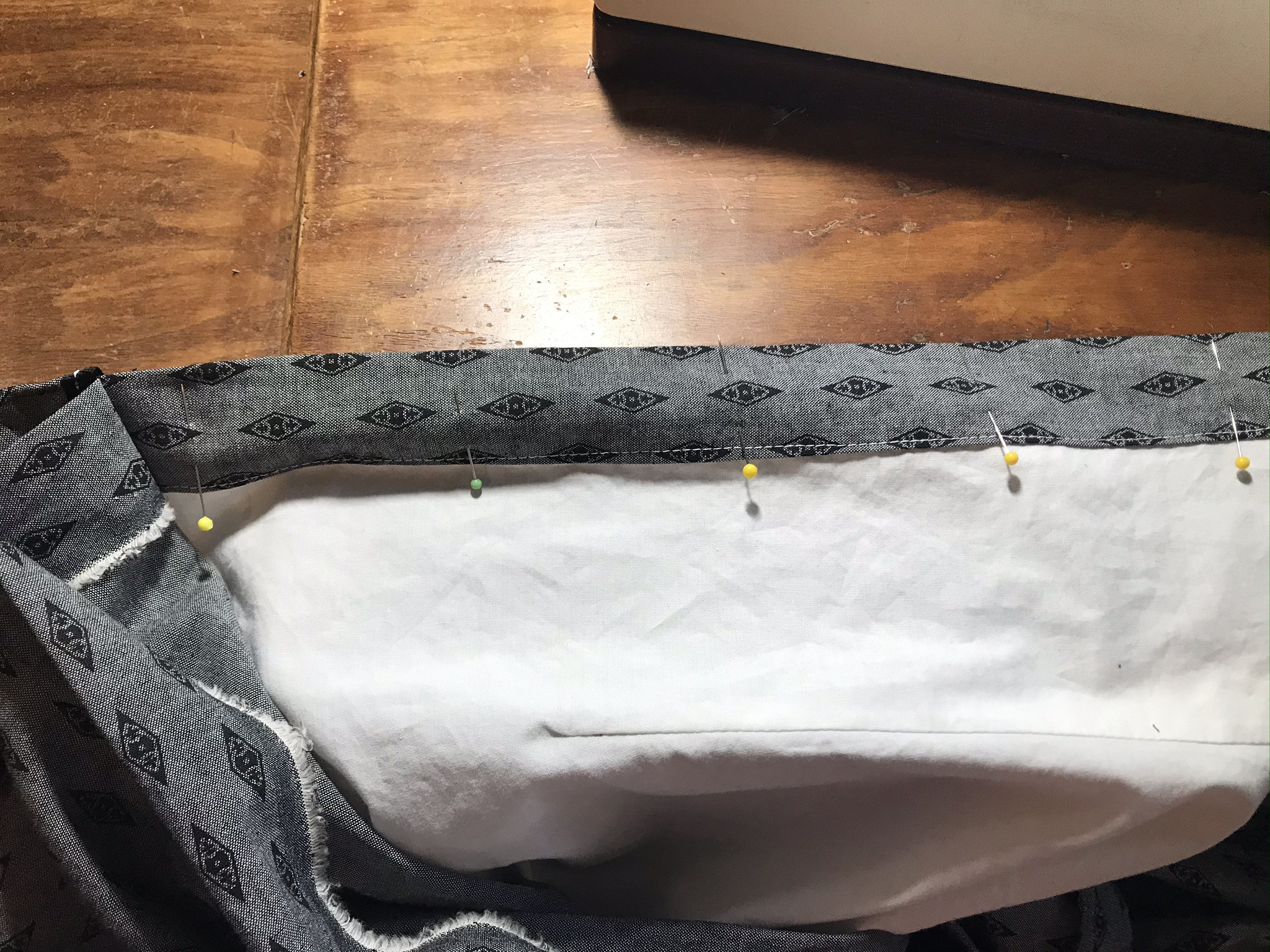

This was a fairly straightforward project. I used my personal sloper that I had already tested as the lining pattern. I drafted the yoke pattern freehand, based on the angles and proportions of the original. I allowed for pleats at center front and center back, just as the original seamstress had done. You’ll notice that I stitched the front of the dress to the lining before applying the yoke.

The original dress collar was made in two sections, with a seam at the center back. This apparently accommodated the unusual method of assembling it, with both lining sections sewn together over the back seam to cover the raw edges. I decided to adapt the pattern to my own sewing style, so the back seam is pressed open and the top collar piece is cut on the fold.

The original dress had a self-fabric facing sewn down along the front edge of the lining to carry the buttons and buttonholes. I copied this detail, which gives the dress a smooth fit over my undergarments and prevents the white lining from peeking out. The outer layer is pleated into the yoke at center front, with a row of buttons. I copied these buttons, too.

The antique garment had several buttons at the lining closure, somewhat randomly spaced. I chose instead to space my buttons evenly. Here’s a helpful hint for positioning five buttons, evenly spaced, without using a measuring tape.

First, locate the positions of the top and bottom buttonholes. Mark these with pins, perpendicular to the edge.

Fold the edge in half, pinching a crease at the center point. Place a pin at the crease to mark this position. Finally, fold each of the other halves to find those centers, creasing and marking. Now all your buttonholes are evenly spaced!

The sleeve pattern I used was from a design that I had already made and knew that I liked. The style is sometimes called a “bishop” sleeve: a full sleeve is gathered into a fitted cuff at the wrist. The original had a narrower bishop sleeve, while my copy had more fullness at the top.

Wearing the House Dress

This is a basic dress (sometimes called a wrapper or a “Mother Hubbard”) that a middle-class woman might have worn at home in the morning. I finished sewing on the last of the buttons at about 9:00 AM, and I wanted to wear it right away! I put it on over my basic Edwardian underpinnings: corset, petticoat, drawers. Under the corset I wore a modern white cotton tee shirt instead of my pretty white cotton chemise. (I was avoiding the work of laundering and ironing it.)

The house dress was comfortable! I wore it the rest of the morning in my studio, and then through lunch and into the afternoon. It was perfect for a break on the porch swing with a ladies’ magazine (a “Modern Priscilla” from 1909). I finally changed out of it at about 4:00 PM.

If it had been 1907, I might have put on something a bit nicer at noon to serve and eat dinner. Or, I might have changed into a street costume after dinner to go out and run errands or visit friends. As it was, I had a quiet day at home, and stayed comfortable all day long.